It is usually said that the roots of the various ryū or “schools” of ninjutsu are in Iga or Koka (Koga), but when it comes to the ninja tactics of the Fuma clan and the ninjutsu employed at Toda Gassan Castle by the Hachiya-Shu of the Amago and Toda clan, they come from neither. This did not surprise me though, because during my research for the Hidden Lineage I had learned that ninjutsu had long been in practice in various places before Iga and Koga had become renown for it. Another interesting fact about these two shinobi groups is that they have the same ancestor. A common blood was between them. They both had descended from the Iborō people.

The Iborō people were immigrants to the Japanese islands and it is unknown as to when exactly they came into the country. There are various theories about them, such as they were equestrian people from the continent, sorcerers who fled from the Korean Peninsula, or people that brought to Japan several useful technical advancements. When they came to settle in Japan, they lived in the San’in region (山陰地方) first. Some researchers even say they possibly become part of the royal families.

However, the San’in district, centered on Izumo (Shimane Prefecture), was often persecuted by the Yamato Imperial Court. A court that had been in power since sometime in the third century. This persecution was due to the fierce resistance of the region to the imperial court’s demands of subjugation. This is often referred to as the “Izumo Country Transfer” 「出雲の国譲り」. It’s a myth on the surface but it is really about invasion and colonization. The Iborō people were a nomadic group. They made their living as travelling medicinal men, ironsmiths, civil engineers and entertainers known as “Okuni” (阿国). They were eventually brought in under the Ritsuryo system, a law system based on the philosophies of Confucianism and Chinese Legalism in Japan which was formed around the 7th century, and they were again subject to persecution by the Imperial Court. Being in the Ritsuryo system meant that all the land formerly owned by the tribes were monopolized by the court and farmland was distributed out to the people to cultivate. Those who got the farmland had to pay a tax to the court and the court paid the royal family a salary from the tax collected. This is how the early imperial court got the people and the tribes under their control. But as the system was based on the premise that “people must settle on the land” the court did not know how to deal with the issue of taxing those who were wanderers. Since they could not come up with a good solution, they labeled them as “luggage” of the state, made them outlaws and classified them as less than human. If they didn’t like it, they had to settle down in a location. But the Iborō people had lived their way of life for a long time and did not agree with changing their lifestyle and culture simply to comply with tax requirements. Many of the people who did take land could not pay the heavy tax and fled. It became a kind of diaspora.

One might wonder how ironsmiths made a living as wanderers. But it makes sense. They would wander through the mountains finding and digging up veins. Civil engineers too would be called to here and there to build bridges and dig waterways. These kinds of people could pretty much go anywhere and find work as long as they had both arms.

Around that time, in the middle of the 7th century, En no Ozuno (En No Gyoja) was born in Nara. It is said he was of a family from Izumo, and even more likely, he was an immigrant from the Korean peninsula, like the Iborō people.

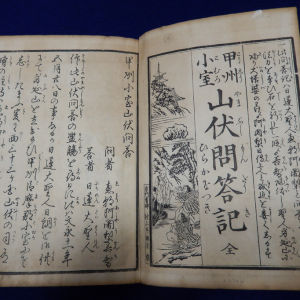

En no Ozuno brought the wanderers and the suffering diaspora under his wing and united them decreeing that “the court is selfish!”. He argued that politics needed to benefit and serve the people. He understood that small guerilla warfare style battles wouldn’t get the results he was looking for. He knew that to change the country he needed to gather the voices of the oppressed. The Iborō people resonating with En no Ozuno’s message, one and all, became his followers, they were to be the prototypes for the mountain ascetics later to become known as shugenja and yamabushi. Over time Ozuno’s followers and supporters grew in numbers, so much so that the court considered them dangerous people who upset the national order and in 699 CE, as their leader, En no Ozuno was banished to the island of Izu Ōshima. Even though he was banished, it appears that the Court continued to think highly of the herbal knowledge that was taught in Ozuno’s school. On October 5th, 732 CE, his student Karakuni no Hirotari was elected as the Head Apothecary (典薬頭), the highest position in the imperial Apothecary (典薬寮).

Due to Ozuno’s exile the Iborō people scattered throughout the country and remained as yamabushi and shugenja until the end of the Heian Period (794 – 1185 CE). The next time the Iborō appear in history will be 200 years later at the battle of Tengyo no Ran in the early to mid-10th century.

Sean Askew – 導冬 Dōtō

Bujinkan Kokusai Renkoumyo

February 5th, 2020

Sources:

歴史民俗学, Issue 20, 批評社, 関東歴史民俗学研究会 2001

忍者の系譜, 漂泊流民滅亡の叙事詩, 杜山悠, 創元社 1972

鬼と三日月 山中鹿之介、参る!, 乾 緑郎 , 朝日新聞出版 2013

遊行と漂泊, 定住民とマレビトの出会い, 山折哲雄, 春秋社 1986

修験道辞典, 宮家準, 東京堂出版 1986

土宗大辞典, 浄土宗開宗八百年記念出版, 浄土宗大辞典編纂委員会 1980